It never ceases

to amaze me how far and wide ships in antiquity could travel. Those

seafarers must have been very adventurous and determined to sail to

unknown destinations.

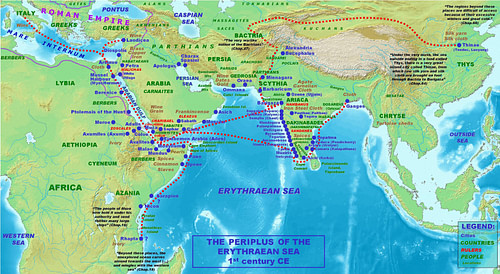

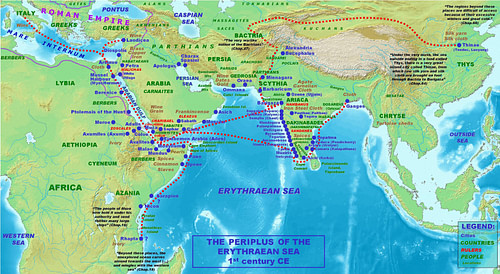

We are far more

familiar with men like Vasco de Gama or Christopher Columbus discovering

faraway lands than Egyptians leaving their hieroglyphs in Australia (The Gosford Glyphs in New South Wales). But

for now, let us stay a little closer to home and trace some of the trade routes

beyond the Mediterranean (see: The flooded remains of Kekova Island), skirting the southeastern coast of Africa, the

southern part of the Arabic peninsula, and Southeast Asia.

A similar itinerary may have already existed in the days of Darius I, who built a canal between 522 and 486 BC that connected

the Nile with the Red Sea (see: The Canal of the Pharaohs, the Suez Canal of antiquity). The foundation stone to

mark the event was discovered in 1866 when the modern Suez

Canal was constructed.

As mentioned

briefly in the present post, the trading activities are based on the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written by a Greek merchant from Alexandria

between 40 and 55 AD. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea has been discussed in detail

by James Hancock in an article published in the World History Encyclopedia,

which highlights the many trade routes and harbors used. The merchant’s diary

is the earliest comprehensive insight into this extensive travel web.

Once Egypt fell into Roman hands in 30 BC, trade

through the ports of the Red Sea increased

dramatically. The principal turnover harbors were Berenice and Myos Hormos, where the goods

arrived on camel caravans from deeper inland. The ships unloaded their cargo

in these same ports from where other caravans brought the incoming goods to

Roman Alexandria

on their return.

Ships heading

for Africa or India, known to leave between July and September, were steered through the middle

of the Red Sea to avoid the dangerous

coastline. Those heading for Africa passed the Horn of Africa and hugged

the coast south to Rapta,

near modern Dar es Salaam.

This voyage took about two years to complete. The trade involved Egyptian

linen, wine, glass, and metal artifacts to be exchanged for African ivory,

tortoiseshell, myrrh, and frankincense. Thanks to the local traders doing

business with India,

the merchants could find cinnamon, Indian fabric, and fine muslin.

The ships bound

for India stopped at the harbor of Aden and

then at Qana

on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula (today’s Yemen),

where they took advantage of the monsoon winds to sail across the Indian Ocean

to India.

Barbaricum was their first harbor near modern Karachi on the Indus River. Here, they unloaded their cargo of Egyptian linen,

wine, glass vessels, silver and gold plates, frankincense, coral, and topaz. In

exchange, they loaded cotton fabric, silk yarn, turquoise, lapis lazuli, indigo,

nard (a kind of spikenard), and other herbs like costus and lyceum (Greek lykion). As the

Romans’ confidence grew, the sailors ventured further south to Muziris on the Malabar

Coast and hence to Sri Lanka.

The Tamils of the island traded their pepper for gold. Black pepper seemed very popular as it constituted about three-quarters of the homebound

cargo! The mainland Indians gladly offered ivory and pearls, whereas silk

and semi-precious stones were brought in from as far as the Valley of the

Ganges and the Himalayas.

It is

astonishing how all this knowledge and trade faded away in the Middle Ages when

men like Vasco da Gama and other intrepid seafarers had to rediscover it.

No comments:

Post a Comment