Erbil or Arbil is the capital of modern Kurdistan, an independent province

in northern Iraq.

In antiquity the city was named Arbela,

situated north of the Mesopotamian plain where the Battle of Gaugamela took place in 331 BC between the armies of Alexander the Great and Great King Darius III of Persia. Erbil claims to be the world’s oldest

continuously occupied settlement (older than Damascus, I wonder?) going back at

least 6,000 years.

To the naked eye, Erbil has very little to offer to the curious archaeologist as many

houses from the 19th and 20th century are cramped inside the old city walls,

right on top of previous constructions. Most everything that is known about

this city comes from ancient texts and sporadic artifacts found at other sites

in Mesopotamia.

Since last year, the first traces of the

ancient city have been revealed thanks to ground-penetrating radar. Two large

structures in the center of the citadel may be the remains of the well-known

temple dedicated to the goddess of love and war, Ishtar, who was consulted by

the Assyrian kings for divine guidance. The Temple of Ishtar

is mentioned as early as the 13th century BC, although it may rest on a much

older sanctuary. It is said that her temple was made to “shine like the day”, a

possible indication that it was coated with electrum (a mixture of silver and

gold) that reflected the Mesopotamian sun.

Slowly these new finds give us an insight into

the history of Arbela and of its

growth since the rise of the mighty Assyrian Empire. This old city was located

on a fertile plain and was the local breadbasket for thousands of years. It

occupied a key position on the road connecting the Persian

Gulf to the Anatolian inland. It is obvious that this prime location

was coveted by many of its neighbors, of which the Sumerians may have been the

first invaders around 2,000 BC. It is here that Alexander the Great

became King of Asia in 331 BC after defeating the Persian King Darius in nearby Gaugamela.

Later invaders were the Romans, Genghis

Khan in the 13th century, the Afghan warlords in the 18th century and the

very recent occupation by Saddam Hussein. Yet, Arbela survived, unlike

other great Mesopotamian cities like Babylon or Nineveh.

Unfortunately during the twentieth century much

of ancient Arbela fell in

disrepair as refugees from the region’s conflicts replaced the town’s people

who moved to more spacious housing outside the citadel. Now that these refugees

also move to more comfortable accommodation, efforts are starting to renovate

the largely mud-brick dwellings. Conservation work enables archaeologists to

dig deeper into the mound, meanwhile listed as a World Heritage Site. With the help of aerial photos taken by the

British Royal Air Force in the 1950’s, American spy satellite images from the

1960’s, and Cold War satellite imagery, combined with the ancient cuneiform

tablets help to pinpoint the best locations for future digging.

It is still difficult to have a good

comprehensive overview of such a long history. As far as we know now, Arbela

was first mentioned on clay tablets unearthed at Ebla

(in modern Syria)

dating to circa 2300 BC. A few hundred years later, rulers of Ur

in southern Mesopotamia claim to have

destroyed the city during repeated and bloody campaigns. By 1200 BC, it is

known that it prospered as an important Assyrian trading post where

copper, cattle, pomegranates, pistachios, grain and grapes were common goods. At

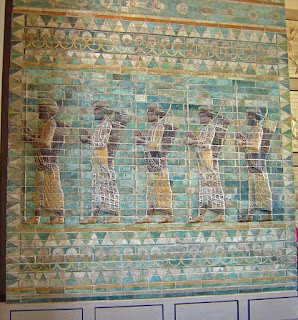

the height of its power in the 7th century BC, Assyria

was ruled by kings like Sennacherib,

Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. A

court poem found in Nineveh praised the city

as “heaven without equal, Arbela!”, and its power is supported

by a stone relief from the 7th century BC found at Nineveh showing the formidable city

walls and arched gate.

By 612 BC the Assyrian Empire was destroyed and

the Medes (maybe the ancestors of today’s Kurds), spared and occupied Arbela,

which was still intact when the Persian King

Darius I came to power about a century later. Soon the Achaemenid Empire

stretched all the way from Egypt

to India till Alexander the Great defeated King

Darius III in the fall in of 331 BC on the plains of Gaugamela.

The Persian king fled across the Greater Zab River to Arbela’s citadel to seek

refuge in the Zagros Mountains where he was

eventually killed by his own men.

Arbela’s oldest fortification had a 20 meters thick wall with

a defensive slope, not unlike the one found at Nineveh, for instance. While most

fortifications were rectangular, the wall around Arbela was a round one,

enclosing both the citadel and the lower town – something we do find more to

the south, in cities like Ur or Uruk.

As houses in modern Erbil

are being abandoned, the archaeologists have a good opportunity to start their

investigations. It is very rewarding to discover a tomb with vaulted chamber of

baked bricks that can be dated to the 7th century BC and definitely is Assyrian.

Using modern technology, some 77 square miles

have been mapped containing some 214 archaeological sites going back as far as

8,000 years! It is not easy to account for a city’s history over such a long

period of time, especially when that city is still being inhabited. After the

Assyrians were gone came the Persians followed by the Greeks, and eventually Arbela

became an essential outpost on the Roman frontier and the capital of the Province of Assyria. With the spreading of

Christianity new communities flourished and the Sassanids ruled till the

arrival of Islam in the 7th century AD.

Even today, Erbil makes the headlines with the conflicts in northern Iraq.

Inevitably a great deal of the city’s heritage is doomed to disappear in modern

warfare, but let’s hope for the best. Maybe, just maybe one day we may discover

the treasures still buried underneath the old citadel and maybe even a small

proof that Alexander and his army were

here some 2,400 years ago.