If you look at the map, Susa is situated almost on the same line as Babylon but away from the Mesopotamian valley, in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains. More importantly, Susa was no more than three kilometers away from the Pasitigris River (modern Karun) which flowed into the Tigris further south and was navigable all the way – a priceless connection to the Persian Gulf.

It had taken Alexander twenty days of a leisurely march to cover the 365 km that separated Babylon from Susa in late November of 331 BC. Here, he installed Sisygambis, Darius’ mother, as well as her grandchildren, who had traveled with him since the aftermath of the Battle of Issus in 333 BC. Curtius and Diodorus mention that Alexander provided teachers for them to learn the Greek language. Nobody ever tells us whether over the years the Macedonian king learned the Persian language but he must certainly have picked up some of it, being as smart as he was.

I have no idea what is left of the city of Susa itself if anything at all. What I find is a scorching hot plateau with neatly reconstructed mud-brick walls up to one-meter high belonging to the palace with at its heart the Apadana. Like its namesake at Persepolis, this Apadana is filled with stubs of columns only. Bits and pieces of columns and their capitals have been piled up together on the side, except for one lonely double-headed bull capital placed under a protective roof. I remember the capital, now at the Louvre Museum in almost perfect condition. My heart aches to look over the remains of this once so grand a palace – hard to imagine what it must have looked like. Interestingly the very stone on which the king’s throne once stood is still in situ.

There are some more remains southwest of the Apadana and it seems that recently one of the entrance gates has been restored, evidently in mud bricks, but without a proper plan I cannot really figure this out. French archaeologists excavated the site in the 1890s and the agreement at that time was that they should leave everything gold and silver in Iran, but that they could take everything else with them. They obviously did. To make things worse (at least in our concept of the 21st century), all the leftover mud bricks and debris were used by the French archaeologists to build their living quarters and storage areas. This building that looks like a castle has been converted into a local museum.

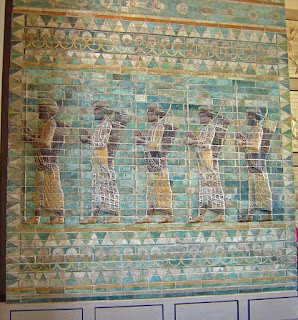

Knowing the superb glazed-brick reliefs that are housed at the Louvre, I find it even more difficult to imagine the splendor and grandeur of this palace in Alexander’s and Sisygambis’ days. After all, it was the setting for the Susa mass wedding that took place here in 324 BC after Alexander returned from India.

Seven years after he had left the Persian Royal princesses in Susa Alexander arranged not only his own wedding but that of about ninety members of his court as well. The stage was set for an elaborate, colossal, and most expensive marriage ceremony. Standing here on the Susa plateau, I wonder where the famous ceremonial tent was set up, most likely somewhere at the foot of this plateau for how else could the ninety-two bridal suites be fitted in, more so since the whole hall was almost half a mile in circumference. In any case, it has been recorded that the hall contained a hundred bedrooms, each furnished with a lavishly decorated bed with linen sheets, and each worth half a talent of silver. Alexander’s bed, of course, had legs of gold – nothing less. The hall was framed and trimmed with sumptuous draperies woven with animal figures and gold thread, hanging down from gilt and silver rods; purple carpets embroidered with gold were spread out. The huge tent was held up by thirty-foot-high columns that were gilded and silvered and set with precious stones.

Alexander sat at the very center surrounded by the other bridegrooms and all his personal friends sat opposite. He took two princesses as his wives, Barsine (renamed Stateira) the eldest daughter of Darius, and Parysatis the youngest daughter of Artaxerxes III. His close friend Hephaistion married Drypetis, another daughter of Darius. The idea behind this marriage was that Alexander wanted their children to be nephews and nieces. The wedding was performed in Persian style; the grooms would have a drink (I suppose a kind of toast) after which the brides were led inside to take place next to their respective husband-to-be. The bridegroom would then take his lady by the hand and kiss her, Alexander being obviously the first to do so. That sealed the marriage.

The ceremonies lasted five days and the banquets were announced by the sound of trumpets. Many entertainers from Greece and Asia performed for Alexander and his noble guests. There was music, songs and recitations, theatre performances with tragedies and comedies in which the greatest artists of those days appeared.

Each of the newlywed couples received a dowry from the king, and on this happy occasion, Alexander even had a special thought for all his Macedonians who had taken Asian wives during his campaigns and granted them a gratuity.

These are the thoughts that rush through my brain as I stand among these scant sun-bleached ruins. There is no sound rising from the city below, no bird, not even a fly to give this site a sense of reality. It seems even the spirits have abandoned the place.

No comments:

Post a Comment