The origin of Ptolemais (or Barca) of the Libyan Pentapolis (see: Apollonia in Cyrenaica (eastern Libya) after Alexander) goes back to the middle

of the 6th century BC. Still, the name Ptolemais was probably given by Ptolemy III Euergetes, the grandson of Ptolemy I, who, in 322 BC, added the city

to his realm after becoming the ruler of Egypt as successor to Alexander the Great. When the Romans annexed

Egypt

in the first century BC, they granted Ptolemais the status of a separate

province. Since the city had no local water supply, the Roman architects managed to bring in water from the surrounding hills and store

it in seventeen huge cisterns under the Forum. It was a flourishing city until

it was hit by the destructive earthquake of 365 AD that caused the entire North

African coast to drop about four meters. The invasion of the Vandals in 428

probably gave the final blow. The Byzantines moved their military governor to Apollonia,

and the Arabs ensured the city was abandoned.

It still looks abandoned today, a mere flat

site thrown with stones and rocks with a sporadic tree to bring in some color.

The access road to ancient Ptolemais is not inviting

either, as it runs through a solid row of abandoned houses that the Italians

built last century – a proper ghost town known as Tolmeitha. It is an eerie feeling to progress over this straight

road flanked by colorful facades with cast iron decorations, which for some

reason, made me think of the Via Appia

in Rome, where

the tombs are replaced by empty houses.

The city of Ptolemais

is no more than a field on a gentle slope from the Mediterranean

up to the mountains, where even the Hippodamian plan is hard to figure out. I

am happy to be pointed to the familiar Decumanus and Cardo once I’ve reached

the crossroad where a piece of wall and a lonely column are all that remains of

the Arch of Constantine from 312 AD.

The Decumanus has been promoted to Monument

Street or Via

Porticata, with on one side the Roman Baths and on the other the remains of

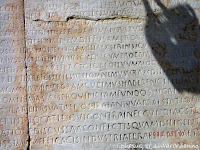

a private house. It was on this road that the Edict of Diocletian from 301 was found setting the prices for the trade

goods now in the local museum.

At the next crossroad, marked with Four Columns,

I turn right to visit the imposing remains of the so-called Palazzo delle Colonne, meaning the “Villa

with the Columns.” Since this is about the only reconstructed building, it can

hardly be missed. The Villa lies here in all its splendor, and it is generally

accepted that it was built according to the then-prevailing fashion in Alexandria (Egypt). This theory is hard to verify

since old Alexandria

is still buried deep under the modern city, and an excellent example of such a villa

has never been found, but I like the idea. In any case, the owner was not a

poor man.

We owe the qualification of Palazzo to the Italian archaeologists of

last century who found that it covered an entire street block (600m2) and counted

two levels. The rear of the building, in fact, the living quarters, is resting

on a plateau from where the owner had a panoramic view over the city, and I can see

all the way to the seafront. This part had an upper level, probably the

sleeping quarters. In front of these quarters below me, there is space for eight

shops opening into the street with, in the back, their own storage rooms. This

storage lies next to a large patio and a complete bathing complex, including a

Caldarium, Tepidarium, and Frigidarium, probably for the master of the house and

his family. A separate staircase leads from the house directly to the patio

below.

The re-erected columns are not well

restored, with big blobs of cement in between, but they give an excellent idea

of the past glory. The leaves at the bottom of the

columns are quite exceptional, a subtle hint to Egypt

– hence the name oecus aegyptius used

to name this room. It takes some imagination to crown these columns with the

capitals (now at the local museum) of the Corinthian order, with Jupiter and Mars' heads staring down from between the acanthus leaves.

Behind this room and in the center of this

complex lies the Atrium, including the earthen pipes that led the water to the bubbling fountain in

the center of the pool. The Atrium was surrounded by a covered gallery

resting on Ionic columns and paved with black and white mosaics, now carefully

covered with plastic and soil. However, the edges are still exposed here and

there. Central in this Atrium is the summer dining room that offers a view

over the inside garden, and the water basin once paved with magnificent

mosaics. More protected from the

elements lies, on the right-hand side, the winter dining room adjacent to the

so-called Medusa room after the mosaic found here, which has also

been moved to the museum.

I am quite impressed by this Palazzo delle Colonne, not only because

of its location, which is striking by itself, but also by the entire

combination of these unique columns with their decoration and paintings, the

many mosaic floors in color as well as black and white, and the many statues that

enhanced these rooms because the Venus and Bacchus from the museum certainly were

not the only ones found here. This Villa, in my opinion, goes beyond what has been found

in Pompeii or Herculaneum,

although they have other characteristics.

The next house block is entirely occupied by

the Forum, paved with small slabs of marble and surrounded by columns, a few of

which have (not too well) been restored. Under this Forum from the second

century AD (in Greek times, this was a Gymnasium), the true treasure of Ptolemais

lies buried: its water cisterns. Eight such huge galleries run north-south over a total length of 50 meters, and nine

run east-west over 20 meters.

I have seen such cisterns in cities like Termessos and Sillyum in Turkey, but not

of this size. The oldest cisterns are from Hellenistic times, and when I climb

down the stairs in the center of the Forum, I can clearly see the marks where

supporting beams held the flat wooden roof of that period. The Romans later

covered the entire system with vaulted ceilings and, in the process, more than

doubled the storage capacity to reach as much as six million liters! It is a unique experience to walk through these vaulted galleries!

Right behind the Forum lies the Odeon – a

somewhat controversial building. Originally built as a Bouleuterion,

this Odeon dates from the 4th-5th century but might as well be a small theatre

since the half-circular orchestra could be filled with water. However, the

water supply is too far away from the theatre to be used as such, and even if

this space could be filled with water, to what purpose was it used? Some

archaeologists opt for miniature sea battles, while others think the water would be used to improve the acoustics. For the time being, this remains

a mystery.

At the far end to the left, on the west

side, one can discern the contours of the Teucheira city gate from the 5th

century AD, but the entire extent in between seems still in dire need of

excavations. Ptolemais definitely was an important city.

On my way back, walking over the westerly Cardo

to the exit, I stopped at the Roman Villa where the mosaic of the Four Seasons was

found (now at the local museum). Not much to see except that this building deserves to be called a

villa. Noteworthy is that the colonnade around the Atrium ends in a horseshoed shape

– an exception to the standard square pattern. Simple smooth columns surround

the central area, neatly restored without the blobs of cement the Italians used

elsewhere.

The local museum is nothing more than a large

storage room, but it is nice to have it so close to the place of excavation

(Now, a few years after the fall of Kaddafi, I wonder what has become of this

place). I marvel at the fine mosaics apparently imported from Alexandria framed by rougher

mosaics laid by local craftsmen. The Medusa-mosaic from the Palazzo delle Colonne steals the show,

next to two fragments with hens and fishes and another large mosaic carpet

showing the Four Seasons with two panthers underneath. True jewels!

Next to a beheaded Bacchus and an elegant Venus

with the head of Demeter (a strange combination), both from the second century

AD and found at the abovementioned Villa, there are several painted and

artistically carved Corinthian capitals revealing the heads of Jupiter and

Mars. Interesting also are the aerial views of the villas I just visited. In a

corner, I find the remains of a sarcophagus with an image of Achilles and, standing behind him, his

mother, Thetis. An intriguing

discovery, although I need help understanding what they are doing here.

One of the masterpieces is the

slightly damaged panel from the Via

Porticata, which shows several goods and their respective prices

according to the Edict of Diocletian

from 301 AD. That such legislation existed at all is quite impressive! Next to it stands a particularly graceful relief with six dancing Maenads found on

the same avenue. The Maenads were a favorite subject in antiquity, and this

relief has enhanced the base supporting a statue of the dramatist Euripides. The original statue was

sculpted in Athens

in 405 BC, but this is the best (Roman) copy. The ecstatic Maenads, followers

of Dionysus, are particularly elegant in their floating robes, waving the thyrsus

staff and shaking their tambourines. Such a pity that in later years, the piece

was used around a well, for otherwise, it is relatively well-preserved.

Once more, this is a city that owes its glory

to Alexander the Great and his

successors as it lived on for another 700 years. Ptolemais definitely

deserves to be added to the list of Alexander’s

achievements.

If we pay more attention than usual,

we find much more than the sites and buildings we are pointed towards. It

happened to me when we drove out of Ptolemais, and I noticed the remains

of a Hellenistic tomb, clearly inspired by the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. It is no more than a lonely square in

the middle of an abandoned field used as a garbage depot, although fenced off with

barbed wire, planks, and corrugated roofing. The original tomb must have been

much higher than the remaining 11 meters, but the floor plan of 12x12 meters is

still intact. This tomb belongs to the second century BC, Ptolemaic times,

and still carries the alternating motives of triglyphs and metopes along the

top edge, although the friezes have since long disappeared just like the steps

at the base. As elsewhere, it was common practice to dismantle old

buildings to reuse the recuperated stone blocks in new constructions (spolia).