Today’s visitors

will inevitably come across many inscriptions when visiting ancient sites or museums. Reading Greek or Latin is not for everybody, and understanding the meaning of the text and context is reserved only for the happy few. The stone or marble

support has more often than not suffered from wear and tear, leaving the

untrained eye to merely guess its value.

We are lucky to

find an explanation next to the inscription, rarely a full translation, as those are

reserved for scholars. Well, the text may be boring, but it also may contain some

exciting twists and turns. Yet, who wants to know?

In antiquity,

people would read the latest laws and decrees, regulations and agreements,

peace treaties, manumission of slaves, grave markers, boundary stones, milestones, etc., as

they walked through public spaces. Some of these texts are still in situ, particularly those engraved on

the walls of still-standing monuments. The majority, however, has found a place

in the museum for safekeeping and is often out of sight.

The most

familiar examples of inscriptions are those chiseled on grave steles,

sarcophagi, and tombs. They also appear on the pedestals of statues lining the

streets, like Phaselis’ Harbor

Street or Olympia’s

road to the Stadium. Others serve to identify the deities, kings, and emperors that

fill the sanctuaries and agoras, or the niches of theatres, stadiums,

libraries, baths, Nymphaeums, and other public buildings.

But some inscriptions will surprise many of us.

For instance, this stele at the Louvre Museum holds the

accounts of the Parthenon Treasury. The text covers both sides of the stele

made of Pentelikon marble and illustrates how democracy works. Athens’

magistrates submitted the public accounts to the citizens for all to see. The

front side, beneath a relief of the Sacred Olive Tree flanked by Athena and the

people (demos), displays the expenses for military operations, religious

ceremonies, and the Panathenaic festival held in honor of their patron goddess

for 410-409 BC. The reverse side has the expenditures for 407-406 BC.

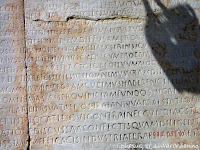

In Butrint,

Albania, a

striking series of inscriptions is carved on the outside walls of the Roman

Theater of Buthrotum, as the city was called in antiquity. They are hard

to read but worth our attention because these are manumissions, slaves who had

gained their freedom for whatever reason. Their sheer number is mind-blowing!

As surprising

and revealing are the Edicts on prices! Who would have thought that there were strict rules to define the prices of goods in antiquity!

Also by Diocletian is the Edict on maximum prices for products and labor discovered in Halicarnassus, dated to 301 AD. The Emperor hoped to stave off a financial crisis and prevent inflation. Although this tablet was unearthed in

Bodrum (the modern name for

Halicarnassus),

bits of similar Edicts were also found in

Pergamon, Aizanoi, Aphrodisias, and

Stratonikea. It is quite surprising to read that the Edict from

Halicarnassus consists of 37 parts. Part 9, for instance, is about shoes and boots … 27

different kinds and sizes are listed!

Taxes are

another matter that deserves attention. One such inscription that is hard to

miss can be seen on Curetes Street

in Ephesos,

close to the Library. This tax law was written in the second half of the 4th

century AD, during the rule of Emperors

Valentian I, Valens, and Gratian.

Less obvious is Alexander’s tax remission from the wall

of the Temple of Athena

in Priene,

now exhibited in the British Museum in London. Alexander contributed to the cost of building the unfinished temple, and in

return, he was allowed to dedicate it: “King Alexander dedicated the temple of Athena Polias”.

This text was followed

by a longer inscription setting out the terms of an agreement between Alexander and Priene under which the

city was to be exempt from taxation. Not all

inscriptions were written in Greek or Latin, and I find it fascinating to hunt

for these exceptions.

Having a closer

look at Lycia’s sarcophagi strewn throughout the landscape, I discovered texts that seemed to be written in Greek but are in Lycian, as they

contain several odd letters that do not exist in the Greek alphabet. Antiphellos and Limyra have good illustrations of Lycian texts.

Another case is

to be found in Sillyum, some 25 kilometers northeast of Antalya,

an often overlooked site, although the hillside is easily spotted in the

otherwise flat plain of Pamphylia. It

takes some detective work to locate the inscription in the Pamphylian language carved in the doorpost of a Hellenistic building – a very rewarding effort

though!

The people of ancient

Side also had a language of their own. A small inscription has survived and can be

seen at the local museum located inside the remains of the Roman Baths.

After Alexander conquered Lycia and Pamphylia, Greek became the lingua franca, and the local tongues

disappeared.