For years I lived with the image of the straight road leading up to the plateau supporting the Palace of Persepolis as described by Peter Bamm in his book “Alexander, Power as Destiny” and I am not at all surprised to find the place exactly as I had pictured it: a 12 meters-high wall on top of which a dozen of tall columns compete with each other for the visitor’s attention.

Alexander must have arrived over this very same avenue some 2,500 years before, welcomed no doubt by Tiridates, the citadel commander. This man had sent a letter to Alexander stating that if he made it ahead of those who planned to defend Persepolis for King Darius III, he would hand the palace and its precious possessions over to him. Alexander didn’t have to think twice about such an appealing proposition and he hurried to Persepolis in order to take over ownership.

The earliest construction of Persepolis goes back to Cyrus the Great in about 518 BC, but it was King Darius I (the Great) who conceived and partially built this man-made plateau 450 meters wide and 300 meters deep where he erected the Apadana, the Tripylon, and the Imperial Treasury. A titanic task that was completed by his son, Xerxes the Great. Later Achaemenid rulers all added their own touch and more buildings, yet each and everyone blended in with the initial style.

Alexander reached Persepolis about the first week of February 330 BC and like me, he must have climbed the double stairway that leads from the broad valley floor to the terrace. It is one of the stateliest steps I ever encountered with an easy rise of 10 cm at the time, 38 cm deep, and nearly seven meters wide. After a first flight of 63 steps to a landing, they make a 90-degree turn to another stretch of 48 steps, 111 steps in all to take you to the top. Unlike similar staircases at the entrance of the Apadana, for instance, these walls are plain and barren. Over the centuries, a tale has grown that the slow rise of these stairs was planned on purpose so the visitors could reach the terrace on horseback, but this theory is totally unfounded since entering the palace of a ruler on horseback was considered to be a grave insult.

Once on the plateau, the only access to the huge complex is through the so-called Gate of All Nations which we owe to Xerxes. For some unknown reason I have the feeling of being in a cramped hallway, but the truth is that it measures nearly 25 x 25 meters – a quite sizeable room, I must admit. It has three doors: the one through which I just entered (west) and the one opposite (east), both 3.80 meters wide and 10 meters high; and a much higher third doorway on the south side leading directly to the Apadana. This gate is also wider, measuring 5.12 meters. Nothing much remains of this gate, however, but evidence has revealed that the doors would have been made of wood covered with sheets of gold and bronze decorated with designs of animals. Hard to imagine!

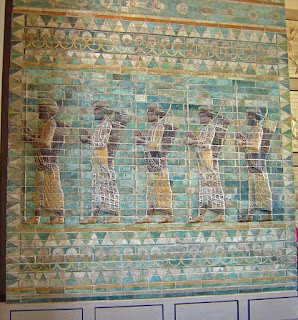

The inner sides of the eastern and western doorjambs of this Gate of All Nations are filled with two enormous bulls standing on a 1.50-meter-high pedestal. The composite animals have the body of a bull, the head of a bearded man in Assyrian style, and the wings of an eagle. Above their backs are cuneiform inscriptions in three languages: Elamite, Old Persian, and Babylonian confirming that Xerxes was Great King by the grace of Ahuramazda. Unfortunately, visitors from later centuries felt the need to write their names there as well – graffiti is of all times it seems. The faces of the bulls looking out over the broad valley are badly damaged but the ones staring out over Persepolis are pretty well preserved, helping to visualize their brothers on the opposite side; originally they were painted in vivid colors (just like Greek statues). What we miss, however, are the very walls connecting the doorways which were built of mud-brick and covered with glazed bricks like those found at Susa and Babylon. It must have been a rather pleasant reception hall.

Although it seems logical to proceed to the Apadana from here, my honest opinion is that Alexander continued straight ahead, over Army Street directly to the Treasury. He had to make sure that Tiridates had kept his word and that the sums of money was indeed there for him to collect.

Today the Treasury is razed to the ground. Only at the far end, we can see a relief showing the audience held by King Darius with his heir Xerxes standing behind him, originally set at the center of the eastern stairway facade of the Apadana. There was an identical relief on the northern stairway of the Apadana and since this one is better preserved, it was moved to the National Museum of Tehran. Why in antiquity these reliefs were moved to the Treasury is not entirely clear, but it seems plausible that when Xerxes became king he didn’t like his place as crown prince behind his father’s throne. Opposite the enthroned king, stands an official of the empire doing obeisance to his king by throwing him a kiss with his hand. It’s an image I have seen repeatedly, not knowing where it came from.

Diodorus mentions that Alexander took possession of the treasury, i.e. the accumulation of the state revenues since the rule of Cyrus the Great. The vaults were packed with silver and gold amounting to 120,000 talents. Alexander kept some of the money to cover his war expenses but the main amount was loaded onto mules and other pack animals to be centralized at Ecbatana. It was Parmenion who was put in charge of this titanic expedition, transporting 7,290 tons of gold and silver from Persepolis, Susa, and Pasargadae with 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels. Just imagine the huge logistics involved in leading such a hoard over a distance of approximately 514 miles, with all their drivers and soldiers to police the precious cargo! Even today, nobody in his right mind would consider undertaking such an operation!

Yet to reach the Treasury, Alexander had to pass the Palace of the One Hundred Columns and if he did not visit it properly upon arrival, he undoubtedly must have stopped here soon after in pure awe. Going by the documented and 3D reconstructions, this building must have been absolutely breathtaking. The sheer size and the multicolored decorations of the columns, ceilings, and walls must have been beyond what he had ever seen (and I say this not knowing exactly how the inside of the Palaces at Babylon or Susa must have looked like as so little has been recovered and those scant remains now scattered among several museums worldwide). The 3D reconstruction uses green and purple as the main colors, but personally, I find the combination rather odd.

The Palace of the One Hundred Columns, measuring 70x70 meters was a military statement made by Xerxes, although its construction was finished by his son Artaxerxes I. Consequently, it is dated between 470 and 450 BC. We find no trace of the original ceiling or walls, and no full-size column is still standing, all we have are the remains of the eight huge access doors with their high reliefs.

The two pillars of the northern doorways are unique with their reliefs of 100 soldiers carrying the enthroned king in a very symbolic relief. The left and right panels mirror each other. Each shows two groups of fifty soldiers in five rows of ten soldiers on one side; with the same on the opposite side, i.e. ten rows of ten, equaling one hundred, which is the same number as for the columns. On the southern doorways, however, we find Artaxerxes I being brought into the hall by his throne-bearers with the Royal Glory (Ahuramazda) hovering above him. A favorite subject used here on the eastern and western doorjambs is that of a royal hero fighting a lion-looking creature with wings and eagle’s feet.

The 14-meter-high columns of this palace are lined up in ten rows of ten each; they excel in their typical style of a bell-shaped base, topped with a round disk on which a fluted cylindrical column is resting; this column, in turn, supports the elaborate flowers that are crowned by the well-known double-headed bulls. It seems that only two of these bull capitals have survived: one is on display in Chicago and the other one is exhibited in Tehran. Foundation inscriptions written in Babylonian were recovered and state that the palace was built by Xerxes and finished by his son Artaxerxes I.

Adjacent and nearly sticking to the Treasury we find a series of smaller rooms that are being attributed to the Harem. I guess they needed a place of their own in this large complex, and a recent archaeological study has revealed that these identical units were, in fact, apartments, in which the rooms were arranged around a four-columned central hall. The Harem is surrounded but sturdy walls, much thicker than any other wall in the palace to protect privacy. There was only one access to the Royal Harem reserved for the king entering from the Palace of Xerxes. Today the area has been converted into a museum with a bookshop, erected in bright red columns. I find it difficult to understand the color and the size of this building when compared to the other palaces on the plateau for somehow it looks like a toy.

The Palace of Xerxes stood seven meters higher than the Harem. Why do I have the feeling that Alexander turned this palace into his headquarters? It had direct connections to the other buildings and at the same time, it gave him enough privacy away from the Apadana and the Palace of the One Hundred Columns. It counted four staircases from where he could directly access the Palace of Darius and the Tripylon towards the north and the Harem through a balcony on the southern side. From this balcony, the king had a splendid view over the entire valley and it just reminds me of the balcony at the Royal Palace of Aegae (today’s Vergina) overlooking the plain below.

This Palace of Xerxes was arranged around the main square hall of 36.5x36.5 m which counted 36 columns set in rows of six each. There were five doorways: two opening into a 12-columned portico on the north; one onto the southern balcony; and two accessing the private apartments. The jambs of these doorways are decorated with reliefs of Xerxes entering or leaving the room accompanied by two attendants, one holding the royal umbrella and the other the towel or the king’s fly-whisk. Xerxes is holding his scepter in his right hand and the lotus symbol in his left. The scene is covered with trilingual cuneiform inscriptions in Elamite, Old Persian, and Babylonian. Like everywhere else, no walls have survived and we have to mentally connect the different doorways to recreate the walls of this palace.

The best-preserved palace of all (and one of the oldest) is the Palace of Darius, leaning against the southern wall of the Apadana (although on a nearly three meters higher level) and diagonally opposite the Palace of Xerxes. It is easy to find the outlines of this palace since all the doorways seem to be connecting to each other. It has a rectangular plan, measuring 40x30 meters. Like the other palaces, it consists of the main hall with twelve columns and both the north and south porticos have columns. The façade of the staircase on the southern side is best viewed from the open space in front of it and reveals two rows of Persian soldiers facing the central cuneiform inscription in Old Persian. Strangely enough, this text was written by Xerxes, who also provided the cuneiform inscriptions at either end of this wall, in Elamite to the right and in Babylonian to the left. The same text is repeated again on the inside of the pillars above. These inscriptions are believed to prove that the Palace of Darius was finished during Xerxes’ reign. The inner wall of the stairways carries cute reliefs of servants and attendants alternatively dressed in Median and Persian dress who actually are climbing the stairs, stepping from one step to the next carrying food and utensils.

Here too the columns are lost but it is interesting to learn that they have been reproduced in the façade of the tomb built for Darius the Great at Naqsh-e Rustam that I’ll visit later. These columns stood on two square bases and were made of wood which was then plastered and colored; like elsewhere, they were crowned with double-headed bulls. In the doorways, we find reliefs of guards in Persian dress holding their wicker shields and long lances. The doorways of the main hall show Darius entering or leaving the room followed by his attendants just like at the Palace of Xerxes. His crown was originally covered with sheets of gold and the holes in the wall are there to prove it; armlets, earrings, torques, and other jewelry were inserted as well. Just imagine what this image must have looked like, brilliantly painted and shining with its gold accessories!

By far the most imposing building is the Apadana, linked to the Tripylon at the very heart of Persepolis. They deserve an attention of their own, so I’ll describe them in a separate post, Alexander amidst the pomp and circumstance of Persepolis.